A parson spills his brandy in this detail from ‘A Harlot’s Progress’, by William Hogarth. Wikimedia Commons.

We’re excited to be sharing our first formal paper arising from Project research at the forthcoming conference Beyond the Coffee House: Masculinities and Social Spaces in the Long Eighteenth Century (QMUL, 5 June 2015). Drawing on our analysis of church court records from the dioceses of Norwich and Chester – which James discussed in this post – the collectively authored paper, and subsequent article, will focus on a fascinating subset of disciplinary cases involving the sociability and drinking habits of the clergy. Here’s our abstract:

Intoxicants, Masculinity, and Clerical Sociability in England, 1680–1740

In September 1722 Christopher Boughton, Rector of Barrow in Suffolk, celebrated the end of harvest time. According to one version of events his harvest men dined in the kitchen; he and his other guests dined in the parlour, and afterwards drank tea and coffee there and walked in the garden to while away the time until evening when the harvest men came into the parlour to sing. The narrative deploys powerful images of the appropriate social roles of an eighteenth-century clergyman, almost stereotypical in politeness, gentility, and deference. But other stories were told of Boughton: of his drinking and ‘making merry’ with his labourers; of his ‘drinking pretty silly healths’; of his regular inebriation in taverns in ‘company’. Accusations of intoxication in a range of social spaces loomed large in the trials of Boughton and other men prosecuted for clerical misbehaviour in the ecclesiastical courts. This paper uses systematic analysis of such cases from the well-documented dioceses of Norwich and Chester to explore expectations and practices of clerical sociability – and intoxicated association more broadly – in the decades around 1700. The clergy formed a distinctive group by dint of function, authority, and education. Yet their professional and social interactions with neighbours and parishioners (male and female) unfolded across contexts beyond the parish church: in households, inns, taverns, and alehouses; at customary and parochial celebrations. That their conduct fell under intense scrutiny allows us to recover their daily sociability within these sites in unusual detail, and – more broadly – to reconstruct with particular clarity the cultural codes that structured drink-related association (especially among males) in the period. At what point did ‘cheerly’ or ‘merry’ drinking by ‘good fellows’ slip over into an excess – of being ‘overcome’ or ‘overseen’ with drink? How flexibly were these boundaries understood? What were the social and physical cues that signalled loss of civility and control? Such questions take us beyond colourful anecdotes about drunk vicars to a greater understanding of the norms that shaped masculine sociability in one of its most ritualised and routine manifestations.

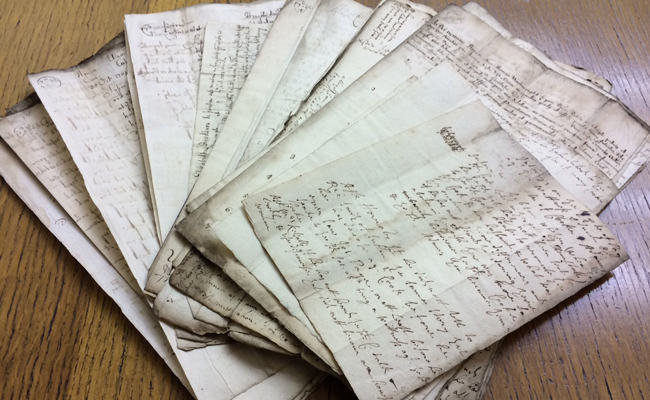

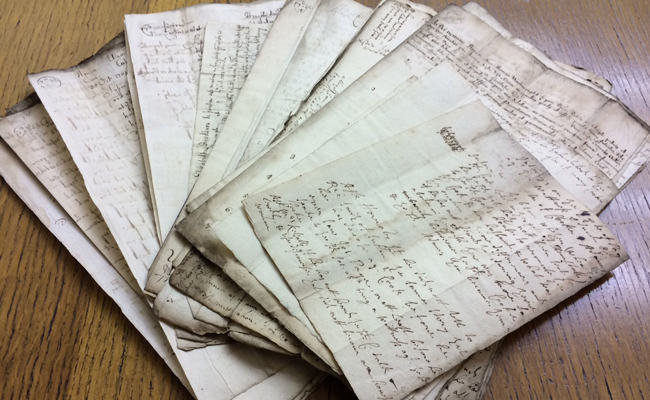

A full case file detailing the ‘irregularities’ of a single rector at Cheshire Archives and Local Studies.

For the programme in full, and to register (which is free), head along to the conference website.

Related Articles

[caption id="attachment_2258" align="alignnone" width="650"] View of Boston from Wikimedia Commons. Woodcut from Wellcome Library, London.[/caption] We’re pleased to announce an intoxicant-themed CFP for the Renaissance Society of America’s next Annual Conference,...

[caption id="attachment_3763" align="alignnone" width="650"] Eighteenth-century engraving of a hookah, or Indian bubble-pipe. Wellcome Library, London (CC BY 4.0).[/caption] [symple_icon icon="calendar" size="normal" fade_in="false" float="left" color="#fff" background="#000" border_radius="99px" url="" url_title=""]Seminar Room A,...

[caption id="attachment_1163" align="alignnone" width="650"] Detail from 'Coastal Landscape with Lighthouse and Ships Anchored in the Bay' (1740). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (CC0 1.0).[/caption] England’s traffic in intoxicants between 1580 and 1740, both...