Detail from ‘Figures in a Courtyard Behind a House’ by Pieter de Hooch (c.1663-65). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (CC0 1.0).

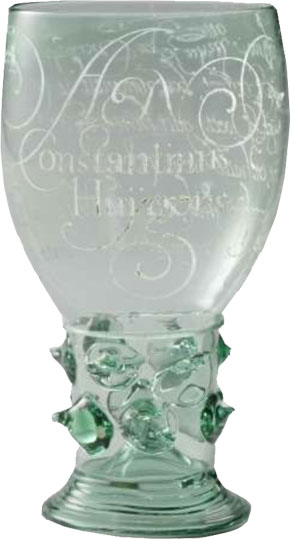

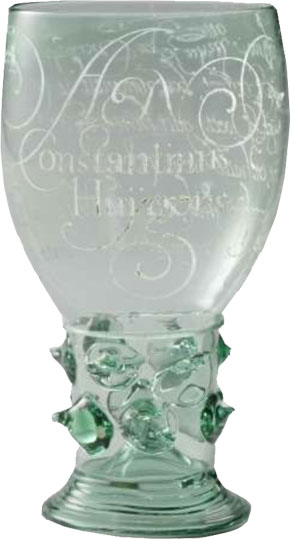

‘Roemer with a poem to Constantijn Huygens’ (1619). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (CC0 1.0).

We’re excited to be organising a one-day workshop on Friday 28 November on ‘Material Cultures of Intoxication: Trade, Taste, and Exchange between the Early Modern English and the Dutch’. Jointly hosted by the V&A and the Netherlands Embassy, and drawing on some of our initial findings in our material culture strand (especially derived from our analysis of port books), the workshop will explore economic, social, and cultural exchange between the Netherlands and England by focussing on intoxicants and the material cultures surrounding their consumption.

Bringing together expert curators and scholars in the Netherlands and the UK interested in broader questions of trade, cultural exchange, and social and ritual practice, a broader aim is to create a dialogue between museum-based scholars and university based researchers. The event is of particular relevance to many of the drinking objects on display in the V&A’s new Europe 1600–1800 galleries (opening in May 2015) – as part of which we will also be mounting a permanent display on ‘Drink, Love, and Loyalty’ – and the glass and ceramic collections of the Rijksmuseum, both under new curatorship.

Programme

10.30–12.00: Panel 1

- Dr Angela McShane (Intoxicants and Early Modernity, V&A/RCA History of Design): ‘What’s in your Dutch Glass? Materiality, Company, and Social Identity’

As the Great Fire of London raged through the narrow, mainly wooden-built streets of London in September 1666, it reduced all the buildings and businesses on Rood Lane in the eastern part of the City of London to cinders. However, in 2008, a team of archaeologists from Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) discovered that, far from destroying everything in its wake, the heat of the Great Fire had caused one wall of a brick-lined cellar in the Lane to collapse inwards, sealing its original contents in situ and largely intact. This paper investigates just one of the many objects that were recovered form that site in its material, cultural and historical context; and uncovers the myriad of meanings that can be found in the bottom of a Dutch glass in London.

- Femke Diercks (Curator of Ceramics, Rijktsmuseum, Amsterdam): ‘A Drink and a Smoke from Dutch and English Delftware’

The sometimes intertwining and often parallel relations between Dutch and English Delftware have been studied extensively in the past. Archival sources help us to understand these relations, as do the objects themselves. Rarely however are specific categories of items from both centers of production compared side by side. A brief survey of the kinds of objects used and developed for the consumption of intoxicants will shed some light on the similarities and differences in production of the vessels and consumption of the goods they were made for.

12.00–1.00: Anglo-Dutch Handling Talk and Gallery Tour

1.00–2.30: Lunch

2.30–4.00: Panel 2

- Professor Jerzy Gawronski (Office for Monuments & Archaeology, Amsterdam): ‘Wine and Tobacco from the Amsterdam (1749): Some Archaeological Evidence on the Transport and Trade of Intoxicants by the VOC’

In 1984 a series of underwater archaeological test excavations were executed in the wreck of Amsterdam. This Dutch East Indiaman beached in 1749 near Hastings on the south coast of England. The archaeological research produced evidence on the packaging and transport of wine and tobacco from the Netherlands to Asia. The provenance of these products could be proved by ecological analysis in combination with historical research in the company’s archives. These archaeological finds are striking examples of the global trade in intoxicants from the Netherlands in the eighteenth century.

- Claire Finn (Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield): ‘Cultural Exchange: Defining the Material Culture of Drinking in the Dutch Golden Age’

The remarkable successes of the Dutch Golden Age were accompanied by significant cultural and social changes. Against an array of new material culture and practices of consumption adopted from distant colonies, inter-European fashion remained at the forefront of design, spreading its influence throughout the material culture of drinking.

4.00–5.00: Afternoon Tea

5.30–7.00: Drinks Reception, Netherlands Embassy

Space at the workshop is unfortunately limited and we are unable to issue a general call for registration, but anyone especially interested in the day’s themes should contact me via e.foxen@vam.ac.uk. A full report of discussions will be available here on the website.